Electrifying internships benefit employer, students and community

Hitachi Astemo

Background

A presence in Greenfield since 1989, Hitachi Astemo established itself as a parts supplier for Honda’s internal combustion vehicles, but it is preparing for a future more focused on electric vehicles.

Traditionally internal combustion vehicles are very mechanical with many moving parts. The electric vehicles (EVs) on Hitachi Astemo’s horizon are electronics intensive with a fraction of the moving parts compared to a traditional ICE vehicle. As you might guess, there’s not much overlap in the two part lists.

That means considerable change is ahead for Hitachi Astemo, and the manufacturer is not waiting to prepare. Most notably, it already is working to address the need for a bigger and more technically skilled workforce, anticipating that its employee base of about 600 workers will grow to more than 1,000 within a few years.

Challenges and Solutions

As Hitachi Astemo leans into an electric vehicle future, it needs to add workers who are ready for a higher-tech workplace. The solution: Internships that bring high school students into the workplace and expose them to various opportunities in advanced manufacturing.

The most obvious challenge facing Hitachi Astemo is the one facing the entire auto industry: the shift from a marketplace dominated by the internal combustion engine (ICE) to one increasingly embracing electric vehicle (EV) technology. The company’s global approach is to balance the demands of both technologies today as it begins to tip the scales toward a future more focused on EV. In Greenfield, the Hitachi Astemo plant is being converted to make EV products such as power inverters but continues to produce ICE products.

While this transition is already reshaping the workforce and requiring more workers, the pipeline for qualified workers is not keeping up. To address the current shortage and long-term needs, Hitachi Astemo seeks to attract young people to careers in advanced manufacturing. A key component in that strategy is the company’s work-experience program.

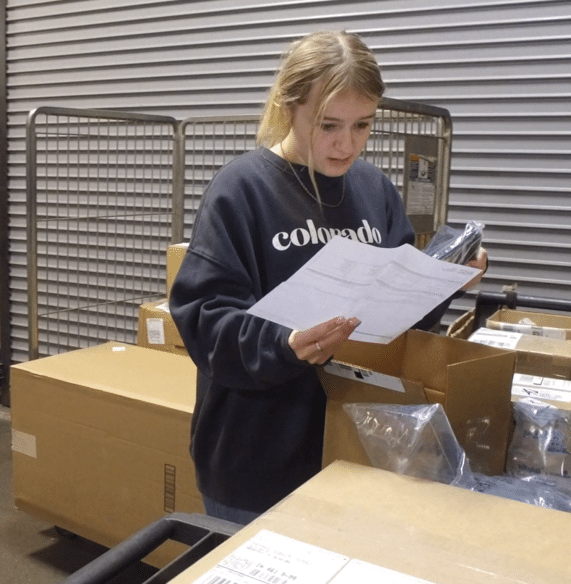

Through a relationship with Eastern Hancock Schools, Hitachi Astemo brings students into its plant for paid internships. Before putting the kids in the shop, Christopher Brunner, Hitachi Astemo’s AM Region Talent Strategy and Marketing Manager, interviews them to understand their academic and career goals – whether they plan on going to college, what subjects interest them, what their long-term aspirations might be and so on – and then puts them into rotations that expose them to areas that fit them well. With a clearly defined structure and roadmap for the interns, the program has a plan for growth that extends into 2026.

As he worked to build the program, Brunner came to the realization that educators don’t understand advanced manufacturing. “They think it’s what Aunt Betty did 40 years ago,” Brunner said. As a result, young people often receive misguided information about advanced manufacturing careers.

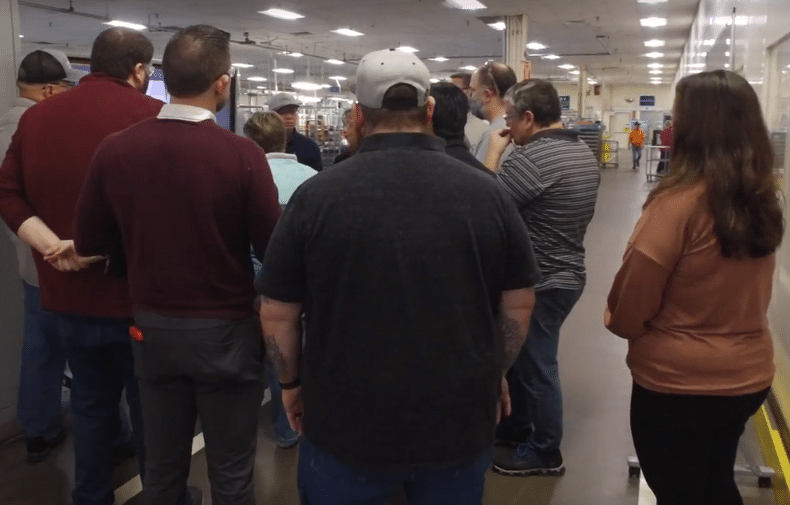

But Brunner doesn’t blame educators for this knowledge gap. He believes that a big part of the onus is on industry, which he says often fails to engage with educators. To tackle this challenge, Brunner invites teachers into the Hitachi Astemo facility so they can see how manufacturing has changed and understand the work that’s being done. “When we bring teachers to our clean room and EV line where kids are working with the equipment and in some cases fixing and programming equipment, they see it differently,” he said.

One hurdle that must be overcome is communication. Essentially, the two sectors speak different languages. The education world can get hung up on certain terminologies that industry representatives might not understand, said Eastern Hancock Superintendent Dr. George Philhower, while Brunner notes that the advanced manufacturing world relies on a lot of buzzwords that don’t translate well for outsiders. Hitachi Astemo and Eastern Hancock schools have found a solution by agreeing to come together and intentionally work past jargon in pursuit of their shared objectives.

Both sides of the equation agree that the objective is much bigger than simply filling jobs. Brunner said he was moved by his discovery that, each year, way too many kids leave Hancock County school systems with no real plan for their future – no college admission, no job lined up, no military enlistment. Also motivated by that fact, Philhower found synergy with Hitachi Astemo’s internship idea. “Chris expressed a high need for employees, and I have kids walking across the stage (to receive diplomas at graduation) with no plan,” Philhower said. “If we can solve both problems, it’s a big win.”

Key Learnings

While cultural disconnects can be a challenge for students and their new work colleagues, Hitachi Astemo workers have been welcoming to the young people, and the benefits of the program go beyond the factory floor.

In its first year, the Hitachi Astemo internship program – which is totally funded by the company – brought four students to the factory for a few hours each school day. Two more were quickly added. Now Hitachi Astemo is talking with additional school systems and has grown the program to 17 students from four school systems this school year. Hitachi Astemo can foresee bringing in as many as 25 to 30 students a year within just a few years. That’s not to suggest the program has been without its challenges.

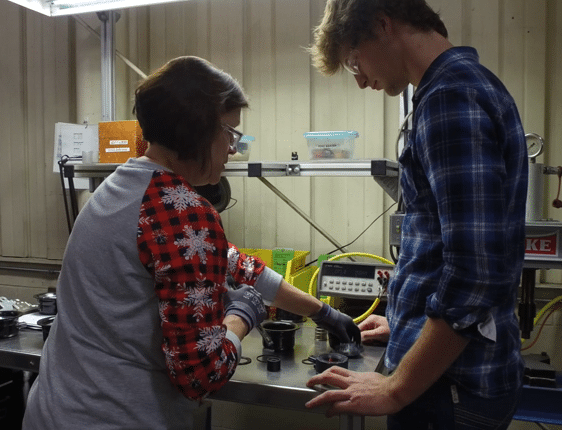

For one thing, the program’s constituents – the students and their coworkers – can encounter cultural disconnects. People in production plants aren’t used to working with 16-year-olds, and teenagers aren’t accustomed to the expectations of the workplace. Overcoming this challenge requires collaboration between schools and industry, as well as clear and intentional communication of expectations.

Despite this potential hurdle, Brunner and Jake Hughes, Head of Hitachi Astemo’s Americas Region ICE Business Unit, have been happy to see how much the company’s current workers – who are typically in their 40s or 50s – enjoy mentoring the teenagers. They appreciate the teens’ enthusiasm and willingness to work, and they seem sincerely interested in passing on knowledge. “There is definitely a welcoming of these students,” Hughes said. “It’s been all positive from the other employees.”

Part of the success of the Hitachi Astemo program is its objective of doing more than simply getting workers into the facility. Both Philhower and Brunner are passionate about ensuring their interns are arcing toward long-term careers rather than jobs, and they take pains to ensure that kids in the program are a good fit and are prepared to get the most out of the experience. “I always tell the student that I don’t know if this program will tell you what you want to do,” Brunner said, “but if I can cycle you through a couple of departments, I guarantee you’re going to find something you don’t want to do, and that might save three to five years of your life.”

The Hitachi Astemo team reinforced that this program is not designed only to create a workforce. “If none of the students come work for us, it’s still a win,” said Hughes. “We’re helping the community.”

Even more important, perhaps, the participants will emerge from the experience with a better understanding of themselves, the working world and their futures. When intern turned full-time employee Gretchen Combs was asked by the Greenfield Daily Reporter about her experience she said, “I came in here, and it’s probably the best experience of my life because I definitely found what I want to do.”

“I came in here, and it’s possibly the best experience of my life because I definitely found what I want to do.”